How it looks the same. And how it really doesn’t. By Toby Manhire.

As the harvest date for some of its farthest-reaching policy promises, 2026 has had plenty of play in the Labour campaign so far. There’s another year, however, that serves its own important purpose, as precedent and inspiration. They talk, a lot, about 2005.

That was an election year, too – one in which Labour won a third term. A few days before the Labour campaign launch a fortnight ago, Labour strategists were quietly mentioning to media that the last time they had held the event at the Aotea Centre was 2005, when Helen Clark took the stage as leader and prime minister.

To drive the point home, Clark herself appeared as the warm-up speaker to Chris Hipkins, and was swiftly alluding to 2005. She said: “I know what it’s like to pull through with enough support, and sometimes just enough support, including from other parties, to form a government.” And: “Leading a party through a tough election is a lot about courage. And Chris Hipkins has spades full of courage.”

Hipkins picked up the thread in the opening beat of his own speech. “As Helen said earlier, we have been here before and we won. And we’re going to do that again.”

The 2005 experience is latched onto as much as anything in seeking to give hope to a wavering base. “It can be done. It can be done,” said Clark at the launch. A few days earlier, she’d put her name to a mailout to supporters. “We won in 2005 after a razor close race because we had the resources to turn out the vote,” she wrote.

Hipkins has been chucking the 2005 example into interviews, “I was here in the 2005 campaign,” he told Newsroom’s Jo Moir, and we went in with everyone saying that we were about to have a change of government, and we didn’t.” (Alongside Hipkins in the Helen Clark backroom were a couple of other names that went on to parliamentary election, Jacinda Ardern and Grant Robertson.)

Commentators have picked up on the theme. “It does have a feel of 2005 about it,” said 1News political editor Jessica Mutch-McKay last week. When, then, are the commonalities? And what are the differences?

How 2005 looked similar

First, a refresher. On September 17, 2005, Labour defied polls and predictions to finish first. In the weeks that followed, Helen Clark assembled a government with support from New Zealand First and commenced a third term for just the second time in the party’s history.

The “third term” bit is half the reason Labour today likes the comparison. The other half is the memory, which lingers still in the minds of many party activists, of wrenching victory from the jaws of defeat. Numbers had bounced around for months, but as the election drew nearer, National looked like the momentum was theirs.

Across the last three weeks before the election, all three polls by Colmar Brunton for 1News put National in front. None of them gave National, or the right, quite the lead, however, revealed in last night’s poll by Reid for Newshub. The jaws of defeat today look bigger, and more tightly clenched.

But the comparisons, as far as Labour optimists are concerned, don’t stop there. It was in the lead-up to this election that the party pulled from the hat a “gamechanger” policy. Scrapping interest on student loans, reputedly the brainchild of Grant Robertson, who was, like Hipkins, and like Jacinda Ardern too, for that matter, a Clark staffer, has increasingly over time come to be seen as the masterstroke what won it. It was the “king hit”, as Kathryn Ryan put it at the time, in “an extraordinary election auction”.

What then is Robertson’s 2023 haymaker? Hamstrung by the fiscal reality – of which more soon – there hasn’t quite been a big bazooka. Robertson’s preferred tax switch, combining a wealth tax with a tax-free threshold, was kiboshed by Hipkins. GST off fresh fruit and vegetables was not it. The extension of universal dental care to under-30s (as of 2026, that is)?

David Seymour certainly judged that was the ambition. “Grant Robertson is attempting to recreate 2005’s election win by desperately bribing voters with ‘free’ stuff,” the Act leader said after the dental pledge, “but New Zealanders are rejecting their cynical and failed policies.”

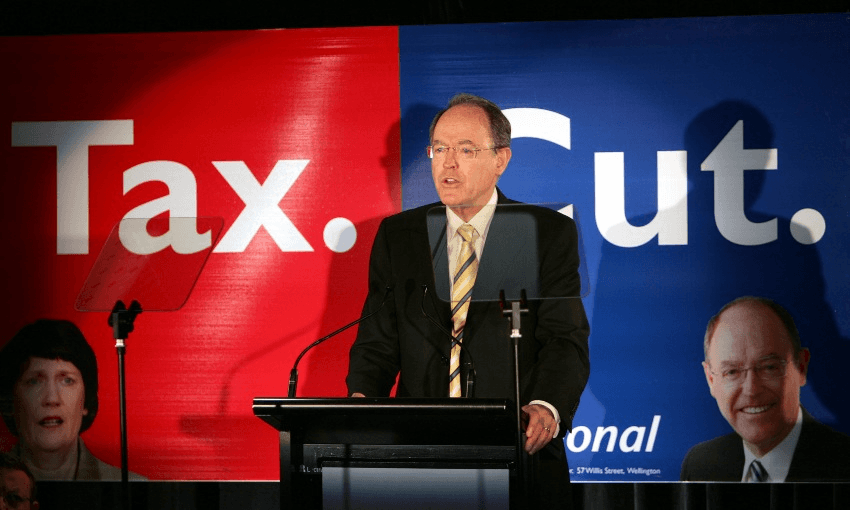

National had at the heart of its campaign in 2005 a promise of tax cuts, as it does today. Then, as now, Labour countered with other measures such as an extension of Working for Families. It argued, and it argues – with limited success – that National’s tax cuts would disproportionately benefit the wealthy and would require corresponding cuts to spending that would imperil essential public services.

There was another key plank for National. Brash had made a splash after a 2004 speech in Orewa that demanded “one rule for all” and asserted Māori were unfairly advantaged. A surge in the polls for National ebbed over time, with many questioning whether Brash’s intervention had harmed social cohesion. In the eyes of many Labour backers, the rhetoric from Act and some in National has had echoes of that time.

Clark, of course, had in the lead-up to 2005 clashed with iwi groups over the highly controversial foreshore and seabed legislation. Separately, she had faced criticisms from the right over the “closing the gaps” programme which sought to redress social and economic disparities for Māori and Pasifika. She would later say that she had not wound back the project. “We didn’t change the policies, we changed the terminology,” Clark said, in comments that arguably could be applied to 2023 Labour’s approach to co-governance.

This was also a scrappy, vituperative election. The most memorable illustration was in the form of National’s billboards, conceived by John Ansell, that juxtaposed Iwi/Kiwi (National’s campaign manager of the time, Steven Joyce, has recently defended the use of the slogan.)

Some of that is mirrored today, though so far the nastiest campaign ad has come from a friend of Labour, the CTU, in its Herald wraparound and digital billboards questioning the character of Christopher Luxon.

Is Luxon a Brash 2.0? There are similarities. Both are parliamentary novices. Brash was made leader of National 15 months after entering parliament; Luxon had been an MP for just 13 months when he began the job. As Brash was then, Luxon has been targeted by Labour as a perceived vulnerability: on trustworthiness and credibility, on experience and strength of character. Labour cast itself by contrast as “trustworthy, capable and strong”, as one of its MPs and strategists, Steve Maharey, later put it.

The goal for Labour then and now has been to depict their rivals, epitomised in the image of the opposition leader, as unprepared for government. As commentator Colin James wrote in The Baubles of Office: The New Zealand General Election of 2005, the Labour argument was that “National, in short, was not quite ready – a judgment shared, in private comments to me, by many in business and even some senior National figures.” While that perspective on Luxon’s National might have been found at the start of the year, not so much today.

Labour supporters might also gaze wistfully at National’s ability to step in a pile of scandal in 2005, most notably when Brash went on BFM and cheerfully admitted to Noelle McCarthy – in contradiction of earlier statements – that he knew in advance about the Exclusive Brethren’s campaign of support.

As to whether Labour might have a scandal ready to drop this time, “If we do, I don’t know about it,” Hipkins told Newsroom. “I’m certainly not banking on that.”

And how 2005 was different

The big difference? The economy, stupid. Today everyone agrees we are in a cost of living crisis. As Christopher Luxon says nearly every day, the most important issue in the election is the state of the economy, and few would argue with that. Treasury’s big announcement today about the state of the books could make for unpleasant reading.

It was different in 2005. Then finance minister Michael Cullen could boast an economy in rude health across most metrics. He had not had to reckon with the unfathomable havoc of a pandemic nor a devastating cyclone. After the election, the defeated first-time campaign manager for National, Steven Joyce, reasoned that “in short, too many people were personally too comfortable economically to make a change”.

In 2023, there is discomfort to burn. The only surprise, perhaps, is that while Hipkins and Robertson have begun to point up reasons to be optimistic that the economy is turning a corner, they have not yet embraced the rhetoric of “green shoots”.

In 2005, the right-track-wrong-track line was pointing up. UMR found that around 58% thought New Zealand was on the right track; 32% thought it was on the wrong track. Recent polling by Talbot Mills, successor to UMR, has the numbers flipped, with 55% saying wrong track and 37% right track.

It was similarly easier for a two-term Labour government in 2005 to make the case on its own record. After a long period of volatility stretching as far back as the 70s, Labour could argue that it had embedded “policies consistent with all New Zealanders participating in a knowledge-based economy and society” together with political stability, wrote Maharey. “We wanted voters to ask themselves why they would change the government when the country was in the best shape it had been in for decades.”

Today, Labour struggles to make the case based on delivery. It can, absolutely, point to progress on child poverty and social housing, as well as the introduction of fair pay agreements. But its signal achievement, paradoxically, it rarely mentions at all. The Covid response, the first half especially but also when regarded in the whole, was the envy of much of the world. But you don’t need a focus group to tell you that people just don’t want to think about all that any more; rightly or wrongly, Labour has decided that on the pandemic every boast comes with an unwelcome ghost.

Then there’s New Zealand First. In 2023, the deal Helen Clark struck with Winston Peters was a shock to many, not least the Greens, who had been working constructively in the lead-up to the election on the basis they’d be in government with Labour.

That was the last and one of the most important tactical plays Labour deployed in 2005. Many thought it remained a possibility this time even after Winston Peters said he wouldn’t be part of a Labour government – there was enough wiggle room left for the old campaigner to thread a needle, should it be required, they said.

But that is surely off the table since Hipkins so emphatically decried and so unequivocally ruled out working with Peters and New Zealand First. Surely.

Another conspicuous difference between then and now is the strength of the major parties. Throughout 2005, even for voters faced with the uninspiring Brash and the patience-testing Clark, National and Labour combined consistently polled more than 80%, as they did on election night.

Today, a mix of disaffection with the big two and the appeal of smaller parties puts their combined total well under 65%. Last night’s poll suggested that might be shifting, at least for National. Their result was the first time any party has topped 40% in any published poll this year, though the “purple vote” was still under 68%.

There is another thing about 2005 that is worth noting. Labour worked extremely hard on increasing voter turnout. Though Labour was beaten in campaign advertising, Colin James wrote in The Baubles of Office, it “produced and on-the-ground initiative which might well have made most or all of the difference of 2% in the vote between it and National”. A mini-campaign targeting state house tenants and voters in Māori seats who had not voted at the previous election saw “a noticeable lift in late enrolments and turnout in Labour’s favour”.

In 2015, that turnout was 81%. True, it was higher still in 2020, on 82%, but can it reach those heights next month? If the lack of enthusiasm for the two main parties translates into a lack of enthusiasm more broadly and turnout falls substantially, it is very hard to see how Labour pulls off anything like a 2005 repeat.

For all the differences, however, polls like yesterday’s are only likely to make Labour cling more eagerly, if not desperately, to the 2005 example. More than anything, to stave off any mood of fatalism, Hipkins might pin to the wall of the war room a media release issued by Fairfax, forerunner of Stuff, three days out from the election 18 years ago. “National is a step away from the Treasury benches,” read the headline. “In one of the final polls due before Saturday, the latest Fairfax New Zealand ACNielsen poll gives National a six-point lead over Labour heading into the final three days of the campaign. Labour has fallen four points in the poll to 37%, while National is down one point to 43%.”