Babylon puts a doctor in the machine

- Published

- comments

Imagine a doctor you could consult at any time, describing your symptoms and then getting a speedy and accurate diagnosis - all in a smartphone app.

That is what British firm Babylon is promising, and to build this perfect doctor it is using machine learning.

It is a technique which is suddenly transforming many aspects of our lives.

Babylon is announcing an investment of £50m to build what it claims will be the world's most advanced artificial intelligence healthcare platform.

Its chief executive Ali Parsa says it will put expert health advice in the hands of smartphone users around the world. "Our scientists have little doubt that our AI will soon diagnose and predict personal health better than doctors," he says.

But he is quick to stress that this will be a help to doctors, rather than a replacement: "No machine can put its hand on your shoulder and say trust me I'm going to take care of you."

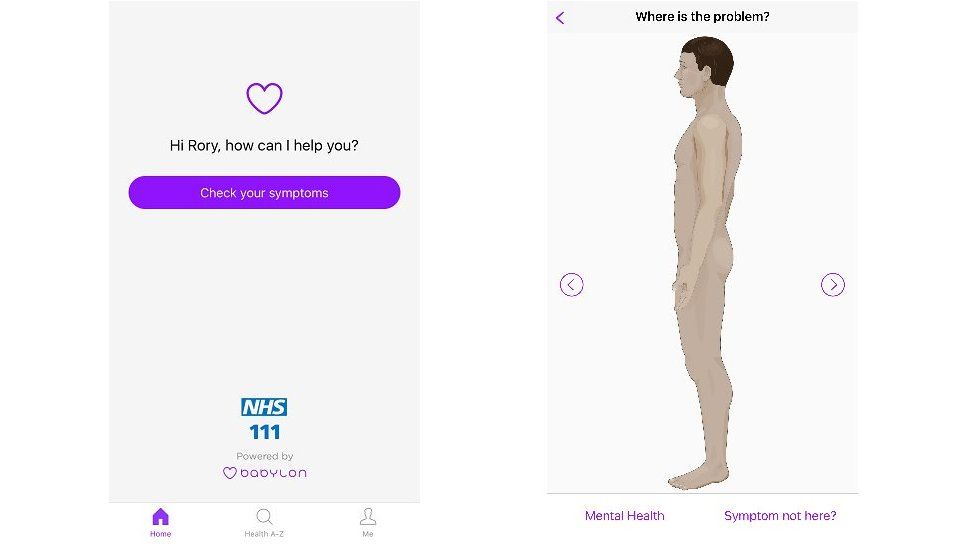

Babylon provides a service where patients can see a (human) GP via their smartphone. Its team of computer scientists and doctors has also built an NHS 111 app which allows some patients in North London to describe their symptoms and then be advised on whether to book an appointment with their GP or take other steps.

Competitive edge

The company is building on the data it has gathered to help its system teach itself to become expert at diagnosing. In effect the machine is going through medical school, armed with vast amounts of data, and learning more every time it interacts with a patient.

"Considering the machine is interacting with thousands of patients a day, the speed at which it is learning is significantly higher than any one individual," says Dr Parsa."We're trying to give the machine a significant amount of data, much more than any human brain can keep, It teaches itself more and more."

Today's report from the Royal Society says the UK has a competitive edge in machine learning, a technique first described decades ago, but which has made rapid progress in recent years ago thanks to greater processing power and access to greater stores of data.

Examples of the technique include Google DeepMind's AlphaGo, which taught itself to beat a champion of the complex game of Go after playing thousands of games against itself. It can also be seen in the rapid improvement in the ability of computers to understand the human voice, to translate from one language to another - and to tell the difference between a dog and a cat.

Ali Parsa launched his app Babylon in 2014

Professor Peter Donnelly, who chaired the panel which spent eighteen months studying machine learning, sees healthcare as one area that could be transformed next: "Analysing complex images and combining information from many sources to help doctors make decisions on diagnosis and treatment will become more and more important."

Excitement - and concern

He says education could be another fruitful area, with machines taking on routine tasks like marking and also producing personalised lessons for individual pupils.

The report warns that action will be needed to give the UK the skills and the investment needed to stay at the forefront of the technology and make sure that everyone across society benefits.

The Royal Society commissioned Ipsos Mori to survey public opinion about machine learning - unsurprisingly only 9% of those questioned had heard of it. But when it was explained that it helped power voice assistants on phones or label photos on Facebook the vast majority said they had used it.

There was also a mixture of excitement about the potential - and concern about possible harmful effects. These included accidents involving self-driving cars, the threat to jobs, and the loss of human contact as the machines get better at fulfilling our every need.

Which brings us back to Babylon's plan to put a doctor in our smartphones.

Healthcare, not just in the UK but in much poorer parts of the world, could be made much more widely available and effective by machine learning.

But persuading patients to talk to a machine - and trust it with their most sensitive information - may take a long time

- Published25 April 2017