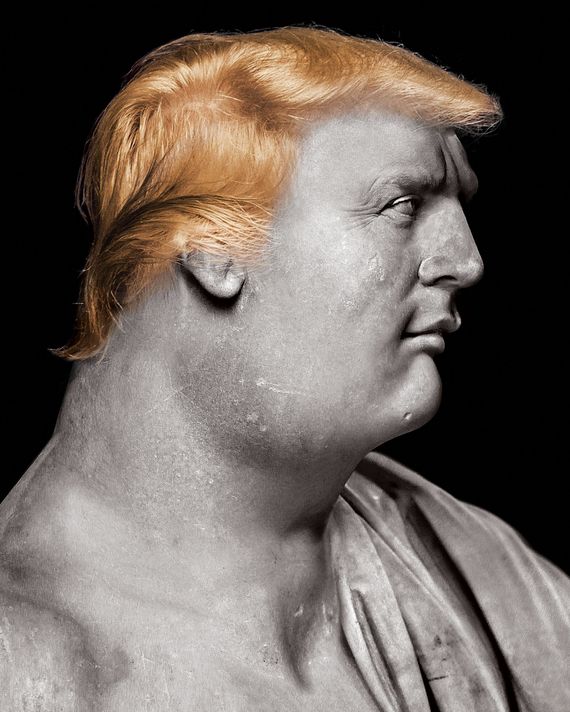

Four years after Donald Trump emerged as the most nakedly authoritarian candidate in American history, it’s tempting to view the threat he once seemed to pose as overblown. Upon his election, some panicked that he would be a proto-dictator, trampling every democratic institution in the fascist manner imported from Mussolini’s Italy and Hitler’s Germany. Others saw merely a malign, illiberal incompetent who would probably amount to nothing too threatening — or believed that America’s democratic institutions and strong Constitution would surely survive Trump’s strongman posturing, however menacing it appeared in the abstract. Many contended that his manifest criminality meant he would be dispatched in short order, with impeachment simply a matter of time.

It was all, unavoidably, unknown and unknowable — and so we cast around for historical analogies to guide us. Was this the 1930s, along the lines of Sinclair Lewis’s It Can’t Happen Here? Or the 19th century in Latin America, with Trump an old-school caudillo? Was he another demagogue like George Wallace or Huey Long — but in the White House?

Well, we now have a solid record of what Trump has said and done. And it fits few modern templates exactly. He is no Pinochet nor Hitler, no Nixon nor Clinton. His emergence as a cultish strongman in a constitutional democracy who believes he has Article 2 sanction to do “whatever I want” — as he boasted, just casually, last month — seems to have few precedents.

But zoom out a little more and one obvious and arguably apposite parallel exists: the Roman Republic, whose fate the Founding Fathers were extremely conscious of when they designed the U.S. Constitution. That tremendously successful republic began, like ours, by throwing off monarchy, and went on to last for the better part of 500 years. It practiced slavery as an integral and fast-growing part of its economy. It became embroiled in bitter and bloody civil wars, even as its territory kept expanding and its population took off. It won its own hot-and-cold war with its original nemesis, Carthage, bringing it into unexpected dominance over the entire Mediterranean as well as the whole Italian peninsula and Spain.

And the unprecedented wealth it acquired by essentially looting or taxing every city and territory it won and occupied soon created not just the first superpower but a superwealthy micro-elite — a one percent of its day — that used its money to control the political process and, over time, more to advance its own interests than the public good. As the republic grew and grew in size and population and wealth, these elites generated intense and increasing resentment and hatred from the lower orders, and two deeply hostile factions eventually emerged, largely on class lines, to be exploited by canny and charismatic opportunists. Well, you get the point.

Of course, in so many ways, ancient Rome is profoundly different from the modern U.S. It had no written constitution; it barely had a functioning state or a unified professional military insulated from politics. Many leaders were absent from Rome for long stretches of time as they waged military campaigns abroad. There was no established international order, no advanced technology, and only the barest of welfare safety nets.

But there is a reason the Founding Fathers thought it was worth deep study. They saw the destabilizing consequences of a slaveholding republic expanding its territory and becoming a vast, regional hegemon. And they were acutely aware of how, in its final century and a half, an astonishing republican success story unraveled into a profoundly polarized polity, increasingly beset by violence, shedding one established republican norm after another, its elites fighting among themselves in a zero-sum struggle for power. And they saw how the weakening of those norms and the inability to compromise and mounting inequalities slowly corroded republican institutions. And saw, too, with the benefit of hindsight, where that ultimately led: to strongman rule, a dictatorship.

So when, one wonders, will our Caesars finally arrive? Or has one already?

Drawing parallels between Rome’s fate and America’s is not new, of course — from Gore Vidal’s trenchant critique of American imperialism in the Cold War, to Patrick Buchanan’s A Republic, Not an Empire in the late ’90s, to Cullen Murphy’s Are We Rome? in the aughts. But the emergence of Trump adds a darker twist to the tale of imperial overreach and republican decline: that the process is accelerating, and we may be nearing a point of no return.

The story of Rome is as unlikely as America’s. Its republic emerged from a period of rule of consecutive kings, elected for life, beginning around 750 BCE, or so later Roman historians claimed. That period lasted a couple of centuries before the last king, a despised figure called Tarquinius Superbus, was overthrown. From then on, from 509 BCE to 49 BCE, the rule of one man was anathema and the title rex a political kiss of death. A Senate and other assemblies replaced the monarch, and power was more widely distributed.

The new offices of state, including the most powerful, the consuls, were all held by at least two people, with strict term limits of one year — and with each officeholder given a mutual veto, to guard against any monarchical pretensions. The power awarded to the consuls and the Senate — representing the landed elite and, increasingly, the business class — was balanced against that of the tribunes (there were, at first, two), representing the masses, who had their own assembly with real clout. A new office of “dictator” was created — a break-glass-in-case-of-emergency assignment to one man to assume total power if civil unrest threatened the republic as a whole. But the dictator had a maximum of six months in office, after which he had to step down.

I’m crudely simplifying a complex and evolving set of arrangements, but the core idea was the dispersal and balancing of power, so that every segment of Roman society, apart from slaves, could have some input, even as the Senate effectively, if not definitively, called the shots. (It was a republic and emphatically not a modern democracy.) What kept this contraption together, without a written constitution, was something the Romans came to call the mos maiorum, the “way of the elders.” Tradition, in other words, or what we would call long-standing democratic norms — adherence to precedent, give-and-take in political negotiations, respect for proper procedures, a willingness to accept half-measures rather than imposing zero-sum solutions, and, above all, loyalty to the republic over one’s own ambition. Whenever someone seemed to push against these norms, they were demonized as a wannabe king.

The erosion of the mos maiorum took a very long time — longer than the entire history of the United States. And it began, in many ways, because of the republic’s success. As Mary Beard’s new classic, SPQR, vividly explores, Rome grew and grew, butting up against and clashing with regional neighbors, waging war, gaining (and sometimes losing) territory in fits and starts. But a political system designed for a relatively small city had to make some serious adjustments as its territory and prosperity and population exploded. The fact that Rome was in a semi-permanent war with its neighbors — a “forever war” if ever there was one — gave military commanders greater and greater clout, and the loot they hauled from Africa to Asia overwhelmingly enriched the elites beyond anything they had previously experienced.

These were decades and centuries of sudden growth in wealth and territory, but also tension. The forever war required small landowners to leave their farms untended for extended periods to fight. Romans saw many of these small estates fall into decay or ruin and begin to be bought up by wealthier landowners and consolidated into vast estates. Over time, as the population boomed and small agriculture waned, food resources became stretched. Before too long, there were too few small landowners to qualify for military service, and widening inequality began to generate increasing resentment among slaves and the poor. And into this fraught moment came the first real populists, the Gracchus brothers, who rose — from within the elites, as Trump and many others have in the millennia since — in the 130s BCE.

The first, Tiberius, elected as tribune of the plebs, proposed a set of land reforms to redistribute wealth. He knew he couldn’t get it past the Senate and so did not even try to, as had been the norm; instead, as Edward J. Watts details in his Mortal Republic, he went straight to the People’s Assembly. Then he tried to get his fellow tribune thrown out of office to avoid his veto, and ran for an unprecedented second term as tribune, at which point several senators, out of procedural tools, organized a small mob, grabbed whatever came to hand, entered the vote-counting arena, and clubbed Tiberius and 300 of his supporters to death.

This kind of violence seems unthinkable in America today, though it was not so unusual in the decades before the Civil War, when senators were repeatedly at each other’s literal throats on the Senate floor. But look past the violence and the situation seems a bit more familiar: deepening polarization, mutual mistrust, abandonment of norms, and trashing of precedents. Soon, it was possible to speak, very roughly, of two Romes: the rich Establishment and the rising masses, the optimates and the populares, waging a zero-sum war through Roman political institutions. In Cicero’s words: “The death of Tiberius Gracchus and even before that, the whole rationale behind his tribunate divided a united people into two distinct groups.” The Latin word for groups is partes.

Tiberius’s cause was taken up by his younger brother, Gaius, who ran for the tribunate, won, and proposed even more distribution of land, new colonies for landless citizens, a major investment in roads and infrastructure, the removal of some senators from juries, and a subsidized grain dole for any Roman in need. It was something for everyone but the elites — and hugely resonant among the populares. This time, the Senate responded more deftly by getting a rival and loyal tribune to outbid and undercut Gaius. In a contentious public assembly on the matter, scuffles broke out, a supporter of the optimates was stabbed with a writing stylus, and a riot was avoided only because of a sudden rainstorm. But the day after, the Senate, deeply rattled, gave authority to the consul to do, as Mike Duncan puts it in The Storm Before the Storm, his gripping account of these years, “whatever he thought necessary to preserve the state.” A bloodbath ensued, in which Gaius was slaughtered along with 3,000 of his followers, their corpses thrown into the Tiber.

In The Storm Before the Storm, Duncan quotes the great Roman historian Sallust, who, looking back, pulled a “both sides” argument — “The nobles began to abuse their position and the people their liberty.” The Greek historian Velleius Paterculus more astutely noted that “precedents do not stop where they begin, but, however narrow the path upon which they enter, they create for themselves a highway whereon they may wander with the utmost latitude.” A cycle of polarization had begun.

As the turn of the first century BCE approached and wars proliferated, with Roman control expanding west and east and south across the Mediterranean, the elites became ever wealthier and the cycle deepened. Precedents fell: A brilliant military leader, Marius, emerged from outside the elite as consul, and his war victories and populist appeal were potent enough for him to hold an unprecedented seven consulships in a row, earning him the title “the third founder of Rome.” Like the Gracchi, his personal brand grew even as republican norms of self-effacement and public service attenuated. In a telling portent of the celebrity politics ahead, for the first time, a Roman coin carried the portrait of a living politician and commander-in-chief: Marius and his son in a chariot.

A dashing military protégé (and rival) of Marius, Sulla, was the next logical step in weakening the system — a popular and highly successful commander whose personal hold on his soldiers appeared unbreakable. Tasked with bringing the lucrative East back under Rome’s control, he did so with gusto, prompting a somewhat nervous Senate to withdraw his command and give it to his aging (and jealous) mentor Marius. But Sulla, appalled by the snub, simply refused to follow his civilian orders, gathered his men, and called on them to march back to Rome to reverse the decision. His officers, shocked by the insubordination, deserted him. His troops didn’t, soon storming Rome, restoring Sulla’s highly profitable command, and forcing his enemies into exile. Sulla then presided over new elections of friendly consuls and went back into the field. But his absence from Rome — he needed to keep fighting to reward his men to keep them loyal — enabled a comeback of his enemies, including Marius, who retook the city in his absence and revoked Sulla’s revocations of command. Roman politics had suddenly become a deadly game of tit for tat.

When Sulla entered Rome a second time, he rounded up 6,000 of his enemies, slaughtered them en masse within earshot of the Senate itself, launched a reign of terror, and assumed the old emergency office of dictator, but with one critical difference: He removed the six-month expiration date — turning himself into an absolute ruler with no time limit. Stocking and massively expanding the Senate with his allies, he neutered the tribunes and reempowered the consuls. He was trying to use dictatorial power to reestablish the old order. And after three years, he retired, leaving what he thought was a republic restored.

Within a decade, though, the underlying patterns deepened, and nearly all of Sulla’s reforms collapsed. What lasted instead was his model of indefinite dictatorship, with the power to make or repeal any law. He had established a precedent that would soon swallow Rome whole.

This was no longer a republican culture protected by an austere elite, but an increasingly authoritarian one, with great military leaders and a handful of wealthy men dominating the political scene through money, legions, and military success. The ancient institutions and customs still existed but were slowly losing relevance. Worrywarts in the Senate and intelligentsia became concerned about strongmen emerging within the system — “The political situation alarms me more each day,” wrote Cicero. Two in particular stood out: Pompey, a hugely successful celebrity general who, at the tender age of 35, was made consul; and an up-and-coming Julius Caesar, rampaging through Gaul and then Britain, besting Pompey’s imperial acquisitions, and generating wide popular enthusiasm.

The two rivals appealed to both of the factions that had now long since defined the political scene — Caesar was a populist, Pompey a true Establishment figure — and as Caesar prepared to return, the Senate, panicked that another civil war was imminent, overwhelmingly voted that each disarm his forces and deliver them to the state. Pompey, who was in Rome, simply took no notice. Neither did Caesar, in Gaul, who crossed the Rubicon. These two celebrity commanders had so many soldiers, had conquered so much territory and won such widespread support, that the Senate had effectively become irrelevant. It could vote, and it did, but its votes no longer mattered.

The civil war that followed lasted four years, spanned several continents, resulted in Pompey’s murder in Egypt and gave Caesar a monopoly of power. He used it on a grandiloquent scale; his parades were beyond sumptuous and displayed the humiliation of his domestic as well as his foreign enemies, as the wider public thrilled to the spectacle. He was granted the position of dictator by the Senate to stabilize the war-torn polity, then reappointed as dictator in 48 BCE for a whole year, and by 44 BCE had been formally named dictator-for-life. At one point, his ally Mark Antony even offered him what looked like a crown.

His assassination — the famous murder on the Ides of March — was accomplished not by a mob but by a group of senators, who feared another rex and worried that their own attenuated power — or the republic itself — would disappear entirely. But it was a last-ditch attempt to save any kind of checks and balances within the system. After years of further civil war, Caesar’s adopted nephew, Augustus, finally destroyed his enemies, shed any pretense of republican rule, and established himself as emperor. His reign would last 40 years. Only emperors succeeded him.

History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes — as Mark Twain is legendarily said to have remarked. There is no chance that rival political-party leaders in the U.S. are going to assemble vast armies and march on Washington to seize total power. We do not have an existing institution, like the Roman dictatorship, that could be instantly used to impose tyranny. Rome had many civil wars across many theaters as the republic staggered to a close — not one, single catastrophic event followed by a contested but permanent settlement. The vast American middle class that stabilized liberal democracy at the height of the 20th century never existed in Rome. We have a welfare state that provides some measure of buffer against popular revolt and a written, formal Constitution far harder to flout brazenly than the unwritten mos maiorum of the Romans.

But still. It’s impossible to review the demise of the Roman Republic and not be struck by the parallel dynamics in America in 2019. We now live, as the Romans did, in an economy of massive wealth increasingly monopolized by the very rich, in which the whole notion of principled public service has been eclipsed by the pursuit of private wealth and reality-show fame. Cynicism about the system is endemic, as in Rome. The concept of public service has evaporated as swiftly as trust in government had collapsed. When the republican virtues of a Robert Mueller collided this year with the populist pathologies of Donald Trump, we saw how easily a culture that gave us Cicero could turn into a culture that gave us Caesar.

Class conflict — which, in America, has merged with a profound cultural clash — has split the country into two core interests: the largely white lower and middle classes in the middle of the country, roughly equivalent to Rome’s populares and susceptible to populist appeals by powerful men and women; and the multicultural coastal elites, whose wealth has soared as it has stagnated for the rest, and who pride themselves on their openness and meritocracy: the optimates. And just as in late-republican Rome, each side has begun not to complement but to delegitimize the other.

The result, as in Rome, is a form of deepening deadlock, a political conflict in which many on both sides profoundly fear their opponents’ power, and in which compromise through the existing republican institutions, particularly Congress, has become close to impossible. Think of Pompey’s and Caesar’s armies not as actual soldiers but as today’s political-party members and activists, mobilized for nonviolent electoral battle and dissatisfied, especially on the right, with anything less than total victory. The battles in this Cold Civil War take place all the time on the front lines of the two forces: in states where fights over gerrymandering and vote suppression are waged; in swing states in presidential elections; in the courts, where the notion of impartial justice has been recast in the public mind as partisan-bloc voting; in Congress, where regular order is a distant memory, disputes go constantly to the brink, the government is regularly shut down, the entire country’s credit is threatened, and long-established rules designed for republican compromise, like the filibuster, are being junked as fast as any Roman mos maiorum.

And the American system has a vulnerability Rome didn’t. We have always had a one-man executive branch, a head of state, with exclusive and total command of the armed forces. There is no need for an office like Rome’s dictator for when a systemic crisis hits, because we have an existing commander-in-chief vested with emergency powers who can, at any time, invoke them. The two consuls in Rome shared rule and could veto each other; what defines the American presidency is its individual, unitary nature. Over the past century, moreover, as America’s global clout has grown exponentially, and as the challenges of governing a vast and complicated country have spawned a massive administrative state under the president’s ultimate control, what was once designed as an office merely to enforce the laws made by the Congress has changed beyond recognition.

So what happens when a populist celebrity leverages mass resentment of elites to deploy that power — as Marius and Sulla and Pompey and Caesar did — in ever more expansive, innovative, and authoritarian ways?

When you think of how the Founders conceived the presidency, the 21st-century version is close to unrecognizable. Their phobia about monarchy placed the presidency beneath the Congress in the pecking order, stripping him of pomp and majesty. No newspaper bothered even to post a reporter at the White House until the 20th century. The “bully pulpit” was anathema, and public speeches vanishingly rare. As George F. Will points out in his new book on conservatism, the president of the United States did not even have an office until 1902, working from his living room until Teddy Roosevelt built the West Wing.

Some presidents rose above this level of modesty. Lincoln temporarily assumed far greater powers in the Civil War, of course, but it was Teddy Roosevelt who added celebrity and imperial aspirations to the office, Woodrow Wilson who began to construct an administrative state through which the executive branch could govern independently, FDR who, as president for what turned out to be life, revolutionized and metastasized the American government and bequeathed a Cold War presidency atop a military-industrial complex that now deploys troops in some 164 foreign countries.

Kennedy — and the Camelot myth that surrounded him — dazzled the elites and the public; Reagan ushered in a movie-star model for a commander-in-chief — telegenic, charismatic, and, in time, something of a cult figure; and then the 9/11 attacks created an atmosphere similar to that of Rome’s temporary, emergency dictatorships, except vast powers of war-making, surveillance, rendition, and even torture were simply transferred to an office for non-emergency times as well, as theorists of the unitary executive — relatively unbound by Congress or the rule of law — formed a tight circle around a wartime boss. And there was no six-month time limit; almost none of these powers has since been revoked.

Some hoped that Barack Obama would wind this presidency-on-steroids down. He didn’t. His presidency began with a flurry of executive orders. He launched a calamitous war on Libya with no congressional authorization; he refused to prosecute those who were involved with Bush’s torture program, who continued to rise through the ranks on his watch; he pushed his executive powers to fix a health-care law that constitutionally only Congress had the right to; and, in his second term, he ignored Congress’s legally mandated deportation of 800,000 Dreamers by refusing to enforce it. He had once ruled such a move out — “I’m president, I’m not king” — and then reinvented the move as a mere shift in priorities. To advance his environmental agenda, he used the EPA to drastically intensify regulations, bypassing Congress altogether. To push his cultural agenda, his Justice Department refused to defend the existing marriage laws and abruptly interpreted Title IX to cover transgender high-school kids without any public debate.

No Democrats regarded these moves as particularly offensive — although partisan Republicans were eager to broadcast their largely phony constitutional objections as soon as the president was not a Republican. And Congress had long since acquiesced to presidentialism anyway, wriggling out of any serious input on the war on terror, dodging the difficult task of amending the health-care law, bobbing and weaving on the environment. And although the worship of Trump is on a whole different level of fanaticism, if you didn’t see some cultish elements in the Obama movement, you weren’t looking very hard. Like Roman commanders slowly acquiring the trappings of gods, presidents have long since slipped the bounds of republican austerity into a world of elected monarchs, flying the world in a massive, airborne chariot, constantly photographed, and now commanding our attention every single day through Twitter.

But Obama was Obama, and Trump is Trump, obliterating most of what mos maiorum remained after his predecessor. Like Pompey, who bypassed all the usual qualifications for the highest office of consul, Trump stormed into party politics by mocking the very idea of political qualifications, violating norms with abandon. He had never been elected to office before; he was a businessman and a brand, not a public servant of any kind; he had no serious grip on the Constitution, liberal-democratic debate, the separation of powers, or limited government. His tangible proposals were slogans. He referred to his peers with crude nicknames, and his instincts were those of a mob boss. But he offered himself, rather like the populares in Rome, as a riposte and antidote to the political and cultural elite, the optimates. A brilliant if dangerous demagogue, he became the first presidential candidate to run not as the leader of a political party, or as a disciple of conservatism or liberalism, but as a fully fledged strongman who promised unilaterally to “make America great again.” It is hard to equate any kind of republican government with a leader who insists, of any American problem, “I, alone, can fix it.”

No one in the American system at this level has ever behaved like this before, crudely trampling on republican practices, scoffing at the rule of law, targeting individual citizens for calumny, openly demonizing his opponents, calling a free press treasonous, deploying deceit impulsively, skirting the boundaries of mental illness, bragging of sexual assault, delegitimizing his own government when it showed even a flicker of independence — and yet he almost instantly commanded the near-total loyalty of an entire political party, and of 40 percent of the country, and this loyalty has barely wavered.

If republicanism at its core is a suspicion of one-man rule, and that suspicion is the central animating principle of the American experiment in self-government, Trump has effectively suspended it for the past three years and normalized strongman politics in America. Nothing and no one in his administration matters except him, as he constantly reminds us. His Cabinet appeared to rein him in for a while, until most experienced adults left it as his demands for total subservience became more insistent. Vast tracts of the bureaucracy are simply ignored, the State Department all but shut down, foreign policy made by impulse, whim, nepotism, for financial gain, or from strange personal rapport with thugs like Kim Jong-un and Vladimir Putin, rather than by any kind of collective deliberation or policy process. Pliant nobodies fill administrative roles where real expertise matters and pushback against the president could have been effective in the past. Congress has very occasionally objected, but it has either been vetoed, as in the recent attempt to curtail U.S. support for Saudi Arabia’s wars, or, if it succeeded in passing legislation with a veto-proof majority, as in Russian sanctions, been slow-walked by the White House.

Writing honestly about this — and the extraordinary upping of the authoritarian ante this presidency has entailed — comes across at times like a dystopian portrait of a nightmare future, except it is very much the present and greeted either with enthusiastic support from the GOP or growing numbness and acceptance by the broader public. The old-school relative reticence of the republican concept of a president had already been transformed, of course, but Trump ramped up the volume to 11: a propaganda channel broadcasting round the clock, with memes almost instantly retweeted by the president, endless provocations to own the news cycle, and mass rallies to sustain his populist appeal. If the definition of a free society is that you don’t have to think about who governs you every minute of the day, then we no longer live in a free society. The press? Vilified, lied to, ignored, mocked, threatened.

When Trump has collided with the rule of law, moreover, he has had a remarkable string of victories. After a period in which he was amazed that his attorney general would follow legal ethics rather than the boss’s instructions, he has now finally appointed one to protect him personally, pursue his political opponents, and defend an extreme theory of presidential Article 2 power. Checked for the first time this year by a Democratic House, he has responded the way a monarch would — by simply refusing, in an unprecedentedly total fashion, to cooperate with any congressional investigation of anything in his administration. Far from being transparent to prove his lack of corruption, he has actively sued anyone seeking any information on his finances. He has declared a phony emergency to justify seizing and using congressional funds for a purpose specifically opposed by the Congress, building a wall on the southern border, and gotten away with it. He has taken his authority to negotiate tariffs in a national-security emergency and turned it into a routine part of presidential conduct to wage a general trade war. And he has enabled an army of grifters and opportunists to line their pockets or accumulate perks at public expense — as long as they never utter a word of criticism.

He has also definitively shown that a president can accept support from a foreign power to get elected, attempt to shut down any inquiry into his crimes, obstruct justice, suborn perjury from an aide, get caught … and get away with all of it. Asking for his tax returns or a radical distancing from his business interests strikes him as an act of lèse-majesté. He refers to “my military” and “my generals,” and claims they all support him, as if he were Pompey or Caesar. He muses constantly about extending his term of office indefinitely, just as those Roman populists did.

Does he mean it? It almost doesn’t matter. He’s testing those guardrails to see just how numb a public can become to grotesque violations of ethical or rhetorical norms, and he has found them exhilaratingly wanting. And he has an unerring instinct for where the weaknesses of our republican system lie. He has abused the limitless pardon powers of the president that were created for rare occasions of clemency, a concept that to Trump has literally no meaning. He has done so to reward political friends, enthuse his base, and, much more gravely, to corrupt the course of justice in the Mueller investigation. The concept even of a “self-pardon” has been added to the existing interdiction on prosecuting a sitting president.

He has also abused various laws allowing him to declare national emergencies in order to get his way even when no such emergencies exist.

Congress has passed several of these laws, assuming naïvely that in our system, a president can be relied on not to invent emergencies to seize otherwise unconstitutional powers — like executive control of legislative spending. This, of course, is not a minor matter; it’s an assault on the core principle of separation of powers that makes a republican government possible. But when the Supreme Court recently lifted a stay on the funds in a legal technicality, where was the outcry? The ruling registered as barely a blip.

The whims of one man now determine much of what happens in what we think of as a republic, where power should, in principle, be widely disseminated. And you don’t just see this in what has objectively happened. You can feel the difference in the culture. Every morning, Washington wakes up and needs to ask only one question to figure out what’s going on, as they did in the royal courts of old: What is the president’s mood today? If that isn’t a sign of a fast-eroding republic, what is?

Some argue that although the president has obviously attempted to break the law many times and lies with pathological abandon, he still hasn’t openly defied a court order, suspended an election, or authorized something as lawless as torture. He talks and walks like a dictator, but in practice, his incompetence and inability to focus or plan or even read saves us. That, it seems to me, misses three things. The first is the president’s rhetoric. What happened to the Roman republic was a slow slide into public illegitimacy, intensified by the way in which elites played by the rules only when it suited them and broke precedents and norms when it came to defending their own interests, complaining loudly when others did the same.

This generated a feeling that the system was rigged, that it made sense to cut corners, or lie, or take care of yourself before you followed the letter of the law. But when the president himself declares the system he works in is rigged, when he opines that electoral fraud is rampant, when he accuses his own FBI and intelligence services of being corrupt, he accelerates this process of delegitimization. And that matters immensely. In politics, words are not separate from acts; words are acts. Republican norms that are constantly denigrated by their purported leaders tend to disappear. And no single figure has done as much damage to that legitimacy in American history as Trump. He does not even feign respect for democratic norms.

The second case against complacency is that a key branch of government that can and should restrain presidential overreach, the judiciary, is being methodically co-opted for the cause of executive power. The authoritarian strain in conservative thought has, since Watergate appeared to cut a malign presidency down to size, come to define judicial philosophy on the right. The notion that the president controls the executive branch, that his autonomy is essential for expeditious government, and that his decisions are empowered by being the sole figure nationally elected by the people as a whole is now close to a litmus test for any judge or justice seeking a career on the right. It is what defines countless judicial nominees and appointments and is the common denominator between Justices Gorsuch and Kavanaugh. With a chance for a third such appointment, the powers of an authoritarian president, with enough public backing to override congressional passivity or demand its support, could reach heights not seen before.

And the third is precedent. If republican virtues and liberal democratic values are a forest of traditions and norms, Trump has created a vast and expanding clearing. What Rome’s experience definitively shows is that once this space is cleared, even if it is not immediately filled, some day it will be. Someone shrewder, more ruthless, focused, and competent, can easily exploit the wider vista for authoritarianism. Or Trump himself, more liberated than ever in a second term, huffing the fumes of his own power, could cross a Rubicon for which he has prepared us all.

A republican president respects how the system works, treats power as if it is always temporarily held, interacts with other agents with civility, however strained, and feels responsible, for a while, for keeping the system alive. Trump simply has no understanding of any of this. His very psyche — his staggering vanity, narcissism, and selfishness — is far more compatible with monarchical government than a republican one. He takes no responsibility for failures on his watch and every single credit for anything successful, whatever its provenance. The idea that he would put the system’s interest above his own makes no sense to him. It is only ever about him.

And the public has so internalized this fact it can sometimes seem like a natural feature of the political landscape, not the insidiously horrifying turn in American political history and culture that it is. If there is a conflict between his and others’ interests, his must always win decisively. If he doesn’t win, he has to lie to insist that he did. Everything in strongman rule is related to the strongman, as we are all sucked into the vortex of his malignant, clinical narcissism. You never escape him, every news cycle is dominated by him, every conversation is befouled, if you are not careful. And this saps the republican spirit. It engenders a kind of passivity. It makes submission feel like a kind of relief.

Is recovery possible? The Roman lesson is that it is in the short term, but that recovery is fragile because norms are so much easier to break than to build, let alone rebuild, and that the longer republican norms are trashed, the weaker they subsequently become. And much depends, of course, on what comes immediately after, whether these compounding trends can be nipped or reversed before they entrench themselves.

In the Democratic presidential field, we already have 24 previews; on the Republican side, there are distressingly few glimmers of any future for the party other than compounding Trumpism through a second term and beyond. There are those on the left who worry about just what could be achieved by an actually competent Trump, but while Republicans have done the lion’s share of damage to the institutions and norms of government consecrated over centuries, the ultimate extent of the destruction wrought by Trump will be determined by the other party — and how it responds to the precedents when empowered.

Some signs are not that encouraging. “As president, I will give Congress 100 days to get their act together and pass reasonable gun safety laws,” presidential candidate Kamala Harris recently tweeted. “If they don’t, I will take executive action. Thoughts and prayers are not enough. We need action.” This 100-days rubric is one of which she seems particularly fond: “As president, I will give Congress 100 days to send legislation to my desk to stop Big Pharma from raking in massive profits at the expense of Americans. If Congress won’t act, I will.” In the Democratic debates in June, Harris even declared that “on day one, I will repeal that tax bill that benefits the top one percent and the biggest corporations in America.” In fact, Biden recently echoed her.

Candidates often exaggerate their powers to get things done when elected president. But I’m not dunking on the senator from California or the former vice-president to say there are no constitutional mechanisms in a republic for Harris to do any of this, and it is remarkable that these comments had any traction at all. And yet ask Democratic candidates more realistically how they intend to enact their agenda and they also talk about removing existing barriers to executive success. The filibuster will be on the chopping block if it impedes wider health-insurance coverage or a much more ambitious climate agenda pursued by a Democratic president. It has now disappeared from Senate votes on Supreme Court justices, weakening the credibility of judicial independence, as justices appear to be entirely creatures of the president and party that elevated them.

And the wider agenda, completely understandable in response to Trump’s and McConnell’s ruthlessness, is to go on the offensive on both policy and process. Since McConnell prevented a sitting president from filling a vacant Supreme Court seat, so should they. Big populist plans — Medicare for All, a Green New Deal — are now accompanied by proposals to overhaul the Supreme Court to prevent Republican judicial sabotage of progressive reform, to abolish the Electoral College to empower majoritarianism behind a future Democratic president, and to give statehood to D.C. and Puerto Rico to blunt the Republican advantage in the Senate. All these involve the kind of tit-for-tat political warfare that also broke out in Rome, for equally understandable reasons, but which, in time, brought autocracy closer.

But Rome wasn’t lost in a day. Its republic took the better part of a century and a half to lose its practices and its soul. Neither will the United States suddenly succumb to a new fascist party. There is space for populist reform — and it may be essential to restore the legitimacy of both capitalism and democracy — but if it is spearheaded by a charismatic cultish leader instead of a more traditional president, if it runs roughshod over republican norms and procedural compromise, if it responds to Trump’s rhetoric and methods by mimicking them, it may compound the problem.

Republics do not suddenly evaporate. The institutions they establish tend to continue — but, over time, in a deeply polarized and increasingly unequal society, they can become less and less potent, as various leaders and their followings fight zero-sum games using the rhetoric of power rather than the dialogue of deliberation. Precedents are broken; habits of mind and behavior erode; the advance of executive power ebbs and flows; but relentlessly, the water line of what is an acceptable level of autocracy rises. In Rome, it took a long while, but there were periods of much quicker erosion, as charismatic figures established a space for authoritarianism that came to be permanent. And then, of course, a sudden and unexpected collapse. In America, the question of whether this history will repeat itself hangs ominously in the air. But that sound you hear in the distance is of future Caesars preparing to make their move.

*This article appears in the August 5, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!